The Bomb Disposal Expert

the story of baader-meinhof.com creator’s father

MAY 14, 1970. A car pulls up alongside the white picket fence of the Institute for Social Issues in Berlin’s exclusive Dahlem neighborhood. Tree-lined Miquelstrasse street is quiet and the air is crisp; it’s 8:30 am.

Two uniformed prison guards escort a hand-cuffed prisoner from the car. Andreas Baader, convicted arsonist, is being allowed to spend the morning studying at the Institute with the famous leftist journalist Ulrike Meinhof. They had been contracted to write a book together exploring the condition of Germany’s disaffected youth.

Chuck Huffman in Vietnam, shortly before duty transfer to head the Berlin Brigade Explosive Ordnance Disposal unit.

Meinhof and Baader quickly set to work in the reading room; Meinhof works the card catalog while Baader writes at a table under the constant watch of the two guards. After a short while a commotion is heard in the hall outside of the reading room. Three women and a man burst in; the man and one of the women are wearing masks. The masked man is sporting a gun in each hand. The two guards are taken by surprise, and a elderly librarian is shot during the commotion. A window is opened, and the four bandits jump with their rescued comrades out and into a pair of waiting cars. The Baader-Meinhof Gang is born.

Berlin was still buzzing the following month when my family moved into its new military apartment on Berlin’s U.S. Army base. Our apartment building on Argentinische Allee was in the Dahlem neighborhood, a half a mile away from the Institute for Social Issues that Andreas Baader had just escaped from.

Our time in Berlin coincided exactly with the Baader-Meinhof Gang’s glorious days on the run. Not long after Baader and his fellow gang members Jan-Carl Raspe and Holger Meins were captured in a bloody shoot-out with police on June 1, 1972 (with Baader’s girlfriend Gudrun Ensslin’s and Meinhof’s capture to follow), my family packed up our apartment and was on a Pan-Am flight back to the United States.

The Baader-Meinhof Gang were not the only homegrown terrorists operating in Germany during this time, however. Directly inspired by the radical praxis of Meinhof and her cohorts, former SDS leader Fritz Teufel helped to form the Movement 2 June terror group (named after the date of Benno Ohnesorg’s killing during an anti-Shah demonstration in 1967). Before Teufel went underground, when he was still a prominent student leader he advocated humorous actions to draw attention to leftist causes. Teufel’s wickedly funny mind (appropriately, “Teufel” means “devil”) conjured up several infamous praxis during the mid-sixties: the most well known being the custard-filled balloons lobbed at the American consulate. By the early 1970s, Teufel’s Movement 2 June had replaced the custard in their bombs with dynamite, placing dozens of devices around West Berlin over a several year period. Once they even tried to blow up my dad.

Chuck Huffman was very good at his job–a job that most people assume only a crazy man would volunteer for. My father wasn’t crazy, though, and neither were the other men who worked in the Army’s Explosive Ordnance Disposal unit (EOD).

Generally the job entailed disarmament and disposal of old ammunition. When Chuck was stationed at Fort Vancouver, Washington in the early 1960s (where he met my mom, Vicki), he would be called out constantly to disable some ancient stockpile of WWI ammunition or nitroglycerin or dynamite that some farmer found on his property. Chuck’s EOD unit was responsible for all explosive ordnance found in the state of Oregon, as well as southern Washington, and parts of northern California and Idaho.

When my father served in Vietnam (1969-1970), he was in charge of an ammo dump at the Long Bin depot, 30 miles from Saigon. As Chief Ammo officer, his job was to maintain control of what was probably the largest concentration of explosive ordnance in the world. The Long Bin depot received and issued almost all of the ammunition used by the Americans during the war.

Though the base was never under attack, it was a tricky job nonetheless. Once, a round of ammunition rusted through and exploded in the white phosphorous compound. As soldiers scattered, Chuck ran in and put out the fire before it could ignite the entire area and create, as he puts it, “a hellacious big fire.” He possibly saved many lives, definitely risked his own, and saved tons of ordnance. White phosphorous is particularly nasty stuff–it burns white-hot when exposed to oxygen. Soldiers burned with phosphor underwent the worst pain imaginable, often only stopped when blood from their wounds covered and cauterized the phosphor. When medics would begin to treat their wounds–reopening them and re-exposing the phosphor to oxygen–it would begin to sizzle again and the intense burning would start all over. Chuck was awarded the Army Commendation Medal for his bravery.

Chuck’s assignment in Berlin the next year promised to be much more pedestrian. In charge of Berlin Brigade’s EOD team (with about eight men working under him), his job was supposed to mostly consist of baby-sitting the American Army arms stockpile in Berlin. His team was also fully trained in nuclear missile disarmament, but Chuck couldn’t–and still won’t–talk about it. His security clearance was so high that he estimates only 200 of the 200,000 Americans stationed in Europe at the time had an equal clearance.

Occasionally Chuck and his crew would test the security of Berlin’s American Consulate. Once Chuck and several of his men dressed up in dark raincoats, grabbed a large flower pot made to look like a bomb, and marched right into the commanding colonel’s office–past several guard posts who simply saluted Chuck and his men as they walked by. “The colonel didn’t know what to think,” says Chuck. “He couldn’t believe it; he thought it was a fluke. So we did it again the exact same way two hours later. We told him that security in his building wasn’t worth shit.”

To be fair, the Berlin Army base could have never been completely secure. Instead of a fenced off compound, the base was almost completely open–the buildings and housing were mixed in with German residences in the Dahlem and Zehlendorf neighborhoods. It was this open nature that Teufel’s Movement 2 June took advantage of when they decided to place a bomb on Berlin’s American Army post in the spring of 1972.

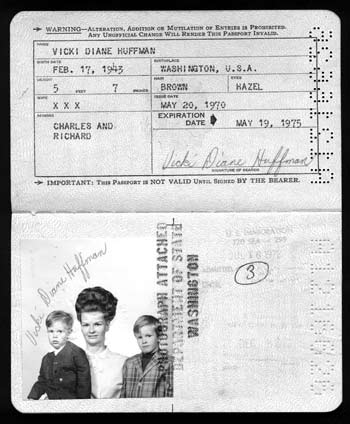

June 1970, Berlin - My mother, Vicki, Brother, Mitch (born: Charles), and myself moved with my dad to Berlin from Vancouver, Washington. We arrived one month after Ulrike Meinhof helped convicted arsonist Andreas Baader escape from police custody. Our home was a half mile from where the indicdent took place.

My first and fondest memories in my life are of Berlin, having lived in Berlin between the ages of two and four. (I was born on March 30, 1968, three days before Baader and his girlfriend Gudrun Ensslin torched a Frankfurt department store). My mom, unlike many of the other wives on the base who preferred to stay insulated in the faux-America that the base provided, actively explored Berlin and the German culture. She attended the Institut-Goethe for five months to learn to speak conversational German. Because my mom was often off wandering through Berlin, I was often put in the base’s Kinder Keller–literally “Children’s Cellar”–which was a day-care center.

One bright spring morning my mom dressed up in her fancy clothes, and her white gloves, and headed for the monthly coffee social of the officer’s wives. She dropped me off at the Kinder Keller, and walked across the street to Harnack House–the Army base’s officer’s club. Before the war, Harnack House was a prominent meeting hall–in the 1920s a young scientist named Albert Einstein first presented his then-radical theory of General Relativity there.

Although Army wives were not technically enlisted in the service, they maintained rank as strictly as their husbands. At the officers’ wives gatherings, none of the wives would get up to leave until the wife with the highest ranking husband got up to leave.

The wives–there were about 50 or so–sat down at large tables in the brightly sunlit main room. Fine linen covered the tables; a German wait-staff served the meals. As the women were finishing their main courses, a man quickly walked up to the ranking officer’s wife and whispered something in her ear. She took a napkin, daubed her mouth, and stood up. Her face was ashen.

“Ladies,” she said. “Get your coats and purses and leave the building. There has been a bomb threat.”

There was no panic: in fact the women rather leisurely went for their things. As Vicki grabbed her coat and headed for the door, she passed her husband, Chuck, running in with several other men.

“What the hell are you still doing in here?” he barked. “Get the f— out!”

She quickly ran across the street and got me from the Kinder Keller and then headed home, her heart racing. While my mom and I waited out the crisis in our apartment (my brother, Mitch, was in school), my dad went to work looking for the bomb.

EOD specialists spent most of their time maintaining the security of explosive ordnance. Occasionally, however, they were called into duty to defuse bombs; this is why my father was at Harnack House. It was a job that they were uniquely suited to do. Trained at the EOD school at the Naval Propellant plant in Indianhead, Maryland (where the FBI’s bomb disposal experts are trained), they were among the best in the world. “I learned how to take apart all kinds of ammunition and make it safe–any ammo from any nationality,” says Chuck. “Mines, shells, bombs–you name it–both terrorist and regular, Army-type bombs.” The only bomb disposal crews that were possibly better than my dad’s crew were the British; at the time they were getting regular practical bomb-disposal experience in Northern Ireland.

He was at Indianhead for six months; six weeks of which he spent learning how to disable nuclear weapons. Usually Army personnel will get hazardous duty pay for serving in a war zone. EOD specialists like Chuck got hazardous duty pay no matter where they served.

Harnack House in 1970, site of the US Officer's club where Chuck Huffman defused a bomb found while his wife and other's were having lunch in an adjoining room.

The Harnack House bomb was found fairly quickly; it was resting on the outside ledge of one of the main hall’s window sills. By today’s standards it was fairly crude–almost quaint in its simplicity. The bomb was encased in a five-gallon clay flower pot. The explosives were at the very bottom, connected to an egg timer and batteries. Covering the whole mechanism was a several-inch-thick layer of putty.

The EOD crew had several methods for defusing the bomb at their disposal, like freezing it with carbon dioxide gas. When the entire bomb reached a suitably cold temperature, the battery would no longer be able to transmit a charge–the wires could be disconnected safely.

Because of the putty, Chuck wasn’t totally sure what he was dealing with inside this bomb, so he didn’t use the freezing technique. Instead he just slowly worked his way through the goop and found the proper wires, and snipped them. The job took a half an hour. The egg timer had about 15 minutes left on it.

Remarkably, my father has never been particularly interested in the origin of the Berlin bombs that he defused. He always assumed that they were left by the Baader-Meinhof Gang, but it didn’t really matter to him. In the course of my research I realized the bombs that my dad encountered were almost certainly planted by Movement 2 June, and not Baader-Meinhof. Chuck greeted the news with a shrug. It was just a job. Chuck can’t even remember how many bombs he defused in Berlin–he thinks there were seven or eight.

Though the Baader-Meinhof Gang was born in Berlin, most of their terrorism was limited to the Federal Republic. West Berlin was therefore left for others. Shortly before Baader’s escape a group of former communards from Fritz Teufel’s Kommune I tried to start their own urban revolutionary unit. Inspired by the presumed success of the Tupamaro urban guerrillas who had seized power in Uruguay the previous year, Teufel and his cohorts dubbed themselves “Tupamaros West Berlin.”

The Berlin Tupamaros had a legal wing, devoted to propaganda, and a self-described illegal wing, dedicated to blowing up the property of their oppressors. Today it seems incredibly naive that the West Berlin Tupamaros thought that their “illegals” could lay bombs throughout the city, and yet have their “legals” remain unmolested by the police. Sure enough, their experiment in riding the edge of society’s boundaries fell apart within a year. From the pieces of the defunct West Berlin Tupamaros emerged Movement 2 June, dedicated completely to underground terrorism.

Not long after the failed bomb attempt at Harnack House, Chuck and his crew were called in to respond to another bomb report; this time at Berlin’s Templehof Airport.

To any longtime Berliner, Templehof was as much a shrine as a working airport. When the Soviets tried to assert control over landlocked Berlin–completely surrounded by Soviet-controlled East Germany–by blockading transportation into the city in 1949, the Americans rescued the beleaguered Berliners with the massive and unprecedented Berlin Airlift. At one point there was one C-47 transport plane loaded with food and supplies landing every single minute for 24 straight hours. The Americans saved the Berliners and stopped Soviet expansion in Europe in its tracks. Even at the lowest ebb of German-American relations, the Berliners continued to love Americans.

One of those C-47 planes was put on public display on the tarmac of Templehof, near a remarkable memorial to the Airlift consisting of a giant partial section of the footing of an arched bridge–symbolizing the Airlift’s “air bridge” to the rest of Germany. It was next to the front tire of the C-47 that someone spotted a bomb on the ground.

My father and his crew hunkered down in the afternoon sun to disarm the bomb. The plane provided some shade relief, but it was still hot work. The bomb was similar to the last one: in a large clay pot, covered in semisolid putty goop.

Chuck had methodically worked on the bomb for about 20 minutes when one of his crew looked up, and peered into the wheel well of the plane. Tucked above the lip of the plane’s skin rested a package–another bomb. “When you have one bomb out in the open and one hidden,” says Chuck, “you know that someone is trying to get you. We assumed that their philosophy on this bomb was that they wanted to get rid of the EOD people and that the plane was secondary.”

Fortunately, Chuck’s crew made short work of the second bomb as well.

In addition to the eight or so bombs that Chuck and his crew were able to defuse, there were many other Movement 2 June Berlin bombs where no advanced warning was phoned in, or the bomb was not discovered in time. Perhaps the most notable bombing was in February 1972, when a Movement 2 June bomb went off at Berlin’s British Yacht Club killing Irwin Beelitz, an elderly German boat builder.

Though they committed virtually as many terrorist acts as Baader-Meinhof Gang, the members of Movement 2 June never received nearly as much publicity. While federal manhunts actively pursued them as well, the Movement 2 June members proved either smarter or more elusive than their Baader-Meinhof counterparts The core Movement 2 June member were not arrested until 1975, three years after Meinhof, Baader, Ensslin, and many of their comrades were captured.

But by then our family was long gone from Berlin. After his tour in Berlin, my dad spent a few years running the ammo depot at Fort Benning GA, before retiring from the military. He then moved on to a new career as a salesperson at Sears for the next twenty years, retiring for the second time in May of 1997. It is perhaps the ultimate testament to my father’s professionalism that twenty-five years after his remarkable time as a bomb disposal expert in Berlin, I find myself much more interested in that personal piece of his history than he is. For my dad, it truly was just a job.